Widely used in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer and other endocrine conditions, aromatase inhibitors are drugs that work by blocking the aromatase enzyme, which turns the androgen hormone into cancer-stimulating estrogen. Until this recent study, no quantitative, noninvasive studies had been performed examining the distribution and regulation of aromatase in living humans.

“This is the first study conducted in living human subjects that surveys the whole body, comparing healthy young and old men and women,” said Anat Biegon, PhD, corresponding author.

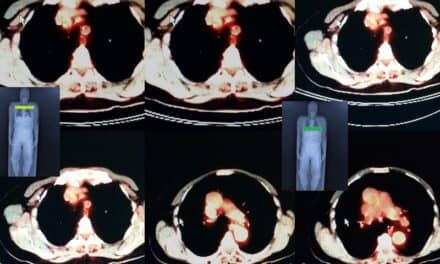

For the study, titled “Aromatase Imaging with [N-Methyl-11C] Vorozole PET in Healthy Men and Women,” 13 men and 20 women were injected intravenously with C-11-vorozole, with PET data acquired over a 90-minute period. Each subject had four scans, two per day separated by two to six weeks. Brain and torso or pelvic scans were included. Young women were scanned at two discrete phases of the menstrual cycle, while men and postmenopausal women were also scanned after pretreatment with a clinical dose of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole. In addition to obtaining time–activity curves, standardized uptake values were calculated for major organs, including brain, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, spleen, muscle, bone, and male and female reproductive organs.

Researchers found that the body organ with the largest stable capacity for estrogen biosynthesis is the male brain, closely followed by the female brain. The study also showed that aromatase availability is slightly but consistently higher in all organs in men relative to women, except for the ovary. Furthermore, aromatase availability in the ovary is linked to the ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle in young women, with increased levels evident in one ovary/cycle around the time of ovulation. The study also saw that aging and cigarette smoke reduce aromatase availability in the brains of healthy men and women.

“Research using in vitro methods indicates aromatase over expression is not limited to breast cancer and is evident in a considerable proportion of ovarian, endometrial, and lung tumors,” Biegon said. “This study provides methodological, baseline, and dosimetry information supporting the use of PET and C-11 vorozole in the non-invasive identification of individuals with disparate disorders who may benefit from treatment with aromatase inhibitors.”

“It also offers the ability to distinguish breast cancer patients who are not likely to benefit from this treatment, reducing unnecessary treatment costs, and adverse effects,” she continued. “Finally, aromatase imaging can be used in monitoring efficacy of treatment with aromatase inhibitors and aid in the development of new drugs in this class.”

According to study authors, radiotracer uptake and the resultant radiation exposure can be sex-dependent, strongly modulated by hormonal status. “Nuclear medicine procedures need to be adjusted for these factors when applied in women,” Biegon said.

Along with Biegon, study authors included David L. Alexoff, Sung Won Kim, Jean Logan, Deborah Pareto, David Schlyer, Gene-Jack Wang, and Joanna S. Fowler.

For more information, visit The Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

Get AXIS e-newsletters free. Subscribe here.