With the right technologies and a sensitive approach, you can address the needs of a growing bariatric patient population and build business.

Hitachi’s high-field Oval 1.5T MRI system features a 74 cm bore.

Hitachi’s high-field Oval 1.5T MRI system features a 74 cm bore.

By Michael Bassett

The figures are alarming.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as of 2010 the percentage of adults in the United States over the age of 19 who were obese was 35.9%. The obesity rate for children and adolescents between the ages of 5 and 19 was over 18%.

And these numbers are trending upwards. The prevalence of obesity among adults was about 15% in 1980 and 23% in 1994, while it has increased in children and adolescents from less than 7% in 1980 and 11.6% in 1994.

These numbers obviously have huge implications for health care in general, and for radiology in particular. The obesity epidemic means that physicians have more illnesses and conditions to treat and image, but, at the same time, the ability to get quality images is compromised by greater body mass.

For example, table weight and gantry diameter limits can restrict the ability of larger patients to undergo CT, MRI, or fluoroscopic scans. Last year, there were reports out of the United Kingdom that the Royal Veterinary College in London was getting requests from local hospitals to image obese patients with its CT scanners that had been customized to accommodate horses.

The good news, according to Raul N. Uppot, MD, assistant professor, department of radiology, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, is that imaging manufacturers “have realized it’s almost a moral imperative that they have imaging and imaging protocols that can address these patients.

“I think as we buy these machines and learn about these protocols, many of the people we have been concerned about are starting to have their needs addressed,” said Uppot.

Clearly, there is a need and a market in the growing bariatric patient population. But providers who want to successfully capitalize on it must be prepared to tackle the challenges, offer the right equipment, and educate patients and referring physicians about its availability.

Ultrasound and X-ray imaging

The imaging approach most limited by obesity, says Uppot, is ultrasound, because of the need for the ultrasound beam to penetrate through tissue. “So when you have a large patient and you need to penetrate through a large amount of tissue, the image quality drops off proportionally according to the thickness of the patient’s subcutaneous fat,” he said.

The situation is similar with x-ray, Uppot says. Since the x-ray has to penetrate through the patient, the larger the patient, the more the radiation and x-ray beam are scattered. Boosting the x-ray voltage and current can increase penetration, but at a cost of reduced image contrast. Increasing exposure time can help image quality, but can cause motion artifact. And increasing both current and exposure time increases the radiation dose to the patient.

Technique is important when it comes to imaging large patients with ultrasound, says Melanie Reed, ultrasound/echo team leader at Baptist Medical Center East in Montgomery, Ala. She says that her team is helped by the portability of the system installed in her hospital about 3 years ago—the Zonare z.one ultrasound system.

The compact footprint of the device means it can be maneuvered around a patient’s bed, so, for example, if Reed is scanning a patient from the right side and has to reach that patient’s left kidney, she can simple move to the other side of the bed and scan with her other hand. “It’s pretty important that you’re able to get to the other side of the bed,” she said. “Otherwise, you’ll have to try to reach around the patient, or even end up lying on top of the patient, which isn’t comfortable.”

New sonographers also are going to be “very challenged” by obese patients, says Reed. “Experienced sonographers know when it’s time to apply more probe pressure, work around the ribs, and try their best to get access from different [acoustic] windows.” She also points out that Zonare’s C-41 transducer is particularly effective for deep imaging in large patients.

CT Scanners

As the press reports from the UK illustrate, CT scanners big enough to handle some obese patients can be difficult to find. And that’s a problem, considering how many medical diagnoses are now made with that modality.

For example, says Uppot, if a patient shows symptoms of appendicitis, CT is the go-to modality because it gives such a good internal view. “But, if someone can’t fit on a CT scanner, options are much more limited,” he pointed out. “You can get a plain x-ray, but that really doesn’t give you a 3D view of the internal structures. Or you can admit the patient and observe them in the hospital and see if the condition worsens, or if there is something clinically brewing, perform an exploratory laparotomy or surgery to diagnose and fix the problem at the same time. So as far as clinical care of the patient is concerned, the drop-off if someone can’t fit on the CT is steep.”

The industry standard weight limit for a CT table is 450 lbs, while the gantry diameter limit is 70 cm. While manufacturers are building larger bariatric CT scanners, they are costly. In a recent article in the Wall Street Journal, an analyst at consulting firm Frost & Sullivan estimated that hospitals can expect to pay as much as 40% more for those larger scanners.

Consequently, many hospitals do not have scanners big enough to handle the biggest patients. Jack Burks, radiology manager at Baptist Medical Center East says there are occasions when the hospital’s scanners can’t handle a patient’s girth. “If a patient can’t fit in our MR or CT gantry, we’ll call around and try to find someone who has a larger bore size,” he said. “There’s maybe one facility within a 150-mile radius [with that size scanner], so it makes it difficult.”

When talking to other radiologists about the subject of imaging and obesity, Uppot says he tells them they should know the weight and size limits of their scanners, as well as where the largest scanners are in their geographical areas. “If there’s a large scanner in their area, they should be prepared to transfer their patients to that facility,” he said.

Knowing about weight and size limits has other implications. Stephen Pomeranz, MD, the medical director and CEO of ProScan Imaging, points out that imaging patients who are heavier than CT or MRI table limits could have serious financial consequences. “You go beyond the weight limit, and you go beyond the table warranty and it breaks, you’re going to have to pay for it,” he said. “And that can cost upwards of $100,000 just for the table.”

Uppot says there are also workflow issues to consider. If, for example, a hospital schedules an obese patient for an examination, but it turns out the patient is too big for the facility’s MRI or CT unit, then, Uppot says, “you’ve wasted your time, your patient’s time, and it affects workflow.” The disruption in workflow also negatively impacts the facility’s bottom line, which is why being prepared to image bariatric patients is so important.

One problem with trying to determine whether it’s possible to image an obese patient is determining a patient’s circumference. “Not everyone knows what their circumference is, and it’s not easy to measure,” Uppot said. One hospital he knows of measures circumference with a low-tech tool—a hula hoop. The hoop is cut in the exact circumference of the hospital’s largest CT scanner so that if a patient approaches the maximum weight limit, but fits within the hula hoop, the CT can be scheduled.

“I thought that was pretty brilliant,” Uppot said, “since it saves tons of time and money, as well as potential discomfort and embarrassment for the patient.” This kind of sensitivity has another benefit: patients will likely remember that the facility’s staff made them feel comfortable. That kind of positive word-of-mouth can go a long way in building referrals and repeat visits.

A complicating issue when it comes to imaging obese patients with CT is the problem of getting good image quality at an acceptable radiation dose.

Don Rucker, MD, chief medical officer for Siemens Healthcare and a practicing emergency department physician, says that when it comes to the radiation dose issue, manufacturers like Siemens have been able to make improvements that maintain and even improve image quality when dealing with the bariatric population. For example, he points to Siemens’ second generation iterative reconstruction algorithm for CT called SAFIRE (Sonogram Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction), which reduces radiation dose and improves image quality by reducing noise in obese patient scans.

MRI

Like CT, the use of MRI in this population can be limited by scanner weight and size limitations. The standard gantry diameter is 60 cm, and the weight limit is 350 lbs. “So MRI bores tend to be a little smaller diameter and sometimes a harder fit for patients,” said Uppot. “But, if you can get the patient up on the table, then you can adjust the MR sequences to get a pretty good image. And manufacturers are coming up with larger bore MR units.”

Some bariatric scanners are available that have bores of 70 cm, and there are also open bore systems that can be used to image larger patients, but the problem with them, says Uppot, is that they generally have lower field strength, which reduces image quality.

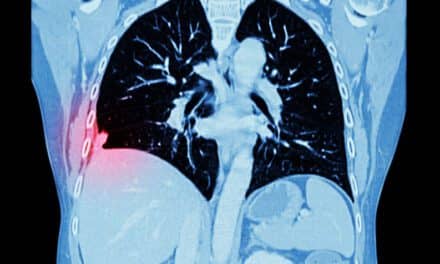

ProScan, which has 24 imaging facilities across seven states (and also provides teleradiology services), recently installed Hitachi Medical Systems’ high-field Oval 1.5T MRI system. With a bore that measures 74 cm, it provides patients with the space and comfort unavailable in smaller, closed systems.

The unit, which was installed in ProScan’s Eastgate imaging center in Cincinnati, Ohio, gives the facility a scanner with more power, more versatility, and better image quality, says Pomeranz. “The ability to accommodate all patient sizes is an across-the-board issue for everything we do in medicine now. So that, and the ability to provide better patient comfort, are also reasons we chose to install it.”

Pomeranz points that MRI is being increasingly important for scanning obese patients because of the “epidemic” of musculoskeletal problems in this population. “There are so many issues in the knees, hips, and ankles that weren’t seen with such frequency before because of the weight these people have to carry around,” he said.

It is also important, he adds, that providers use MRI in such a way that they can successfully characterize which of these problems are fixable, and which are not. “If you perform an operation that’s not going to fix a knee problem in an obese individual, then you have even bigger issues to worry about,” he said.

A Benefit to Patients and Hospitals

Marketing the fact that you have the right equipment to image obese patients—with both referring physicians and direct to patients—can give a provider a competitive edge with this population.

Rucker suggests that many obese patients, because they have undergone orthopedic procedures or have other ongoing medical issues that require MR reimaging, are educating themselves about MRI accessibility. “Patients learn where the machines are,” he said. “Many of them have had prior imaging studies, so they have a sense of where they have to go. So, we’re starting to see there is some learning happening on the part of the patients.”

Uppot agrees that it’s important that patients understand the limits of what some hospitals can offer when it comes to imaging obese patients. “Hospitals will do everything they can to address the issue, but they need to be aware that they can be too large for imaging equipment.”

Hospitals also should realize there are benefits to be had if they are able to image every patient. If a number of patients are being turned away because they can’t fit on a scanner, he says, “then maybe there should be talk about investing the next round of money in a larger scanner than, say, a faster one, since there is an economic and patient benefit if at least one hospital scanner can accommodate these patients.”

###

Michael Bassett is a contributing writer for Axis Imaging News.