Abnormal results on a nuclear stress test are associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiac-related deaths, especially among people with diabetes, according to a multi-center study published in the journal Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. Researchers say the study results support a role for PET myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) in improving cardiac risk stratification in people with diabetes.

PET MPI has emerged in recent years as a promising diagnostic and risk assessment tool. The test uses radioisotopes and a special camera to show how well blood is flowing in the heart when it is under stress. Prior research backs the test’s use in evaluating individuals with suspected or known coronary heart disease. However, less is known about its value among patients with diabetes.

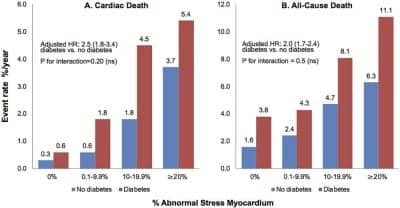

Figure: Bar charts show annualized rates of, A, cardiac death and, B, all-cause death stratified according to percentage abnormal stress myocardium category in patients without and patients with diabetes. Within each scan category, patients with diabetes demonstrated a higher risk of cardiac death and all-cause death than did patients without diabetes. The risk of cardiac death and all-cause death increased significantly with worsening scan category. Numbers in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. HR = hazard ratio, ns = not significant.

In the largest study of its kind to date, investigators at four centers collected clinical data on stress tests for both diabetic and non-diabetic patients and then followed them to track the occurrence of adverse events like heart attacks. The study group consisted of 7,061 participants, including 1,966 people with diabetes.

The data showed that among diabetic patients an abnormal PET MPI was associated with increased risk of cardiac death in all important clinical subgroups based on age, gender, obesity, or those with prior revascularization procedures like angioplasty. Using the data, the researchers could more accurately assess the cardiac risk for a significant proportion of diabetic patients.

“The data from the stress test among diabetic patients actually allowed us to better risk-stratify people in greater than 39% of the cases,” says study lead author Hicham Skali, MD, MSc, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. “Patients with diabetes remain at a significantly higher risk of cardiac death compared to patients without diabetes, and the data from a stress test helps us further stratify those at greatest risk.”

The results suggest PET MPI could help select which vulnerable patients may need immediate treatment while sparing others from unnecessary procedures. Among people without diabetes, the study findings echoed those of previous studies that showed men face a significantly higher risk of cardiac death than women. But that wasn’t the case among diabetic patients.

“In patients without diabetes, being a woman confers a certain advantage in that their risk of death is much lower, regardless of their stress findings,” Skali says. “However, when you look at patients with diabetes, men and women have relatively the same risk of cardiovascular death, and that risk increases with worsening findings on the PET stress test.”

The data also revealed that, even when they had normal PET MPI results, people with diabetes had a similar rate of cardiac death to people without diabetes who were 10-15 years older, suggesting that younger diabetic patients may require additional tools for risk stratification.