A United Front?

By Elaine Sanchez Wilson

In the mid-’80s, as mammography screening started gaining ground in the United States, the country saw its breast cancer death rate drop by 35 percent, according to the National Cancer Institute. However, these days, the technology’s imperfections are at the crux of two hot-button issues in Washington.

Specifically, the breast imaging community is overwhelmingly united against recently proposed screening guidelines from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Meanwhile, a federal bill to establish a national standard of density reporting has fueled much debate within the community.

Screening Guidelines

In April, the USPSTF issued draft breast cancer screening recommendations at the behest of the Department of Health and Human Services. Generating much alarm from breast imagers and affiliated societies, the task force’s proposed guidelines can effectually remove insurance coverage for routine screening in women ages 40-49. In women ages 50 to 74, the task force recommended screening only every other year.

Particularly, the ACA requires private insurers to cover exams or procedures assigned a grade of “B” or higher by the USPSTF. The task force gave routine screening of women ages 40 to 49 a grade of “C” and gave a “B” grade only to biennial screening for women ages 50 to 74.

The response from the imaging community was swift and critical.

“We believe that the Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) can clarify now whether adoption of these USPSTF recommendations would mean that private insurers no longer have to cover mammograms for millions of women 40-49 who, together with their doctor, choose to have regular mammograms and those 50-74 who choose to be screened annually,” said Bibb Allen, MD, FACR, chair of the American College of Radiology Board of Chancellors. “We call on her to affirm that coverage will not be affected.”

In fact, the ACR points out that every major American medical organization with expertise in breast cancer care, including itself as well as the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Cancer Society, National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers and Society of Breast Imaging, recommend that women start getting annual mammograms at age 40.

Breast imaging clinicians are particularly frustrated with the task force’s attention to a pair of Canadian national breast screening studies,[i],[ii] whose data is based on mammogram technology from the 1970s. “I think most people would say those two studies were poorly designed, poorly executed, flawed, and have been discredited for many years,” said Elizabeth Anne Morris, MD, president of the Society of Breast Imaging and chief of breast imaging services at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Moreover, she noted that a lack of transparency exists during the task force’s process of determining worthy studies to evaluate.

“They don’t follow Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines, so it is pretty opaque to those of us on the outside,” she said. “It’s not a real transparent effort.”

Echoing Morris’ opinion, the ACR and SBI wrote in a joint statement, “No breast cancer experts sit on the task force that created these recommendations. The USPSTF did not allow participation of breast cancer or breast screening experts at meetings where evidence was reviewed. The lack of transparency does not meet the IOM standard. These recommendations should be regarded as suspect until experts recognized by major organizations in this area of medicine are included in a meaningful way in their creation.”

Morris pointed to the multilevel repercussions of the task force’s restrictive guidelines. One consequence is the many more thousands of lives lost, she cautioned. Even further, “you’re really looking at an increase in treatment if you’re not going to screen because if you don’t pick up cancers early, you’ll be given more toxic and expensive chemotherapy,” Morris continued. “You will be doing more expensive surgery because the cancers are going to be bigger and presenting at a later stage. And there’s the potential that you may be giving more radiation as well. It seems like these downstream effects never enter into the discussion.”

For Morris, she is most concerned with the recommendation in the guidelines not to guarantee coverage for 40- to 49-year-old women. “The thing that stresses me out the most is the 40- to 49-year-old age group, where we know that annual screening saves lives,” she said. While the task force does admit that screening for this population does affect mortality, it reasons that that the harms outweigh the benefits. Morris, however, cited that removal of screening in this age bracket might lead to six or seven thousand women dying each year for breast cancer. Plus, there are other negative impacts to society at large. “It’s a bigger impact to family, to society, if a woman in her 40s dies of breast cancer, compared to someone later in age,” she said.

The SBI will continue both to advocate for its patients and to realize its mission of education, Morris said. “We need to educate women — our patients — about what this means to each of them,” she said. “And we need to also educate our membership so that they can respond to these new guidelines with accurate information and talking points.”

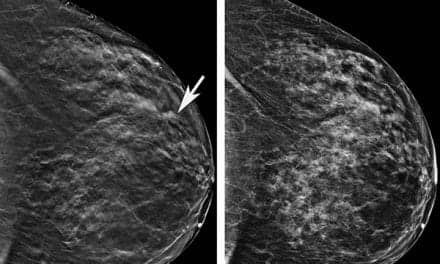

“We do know that mammography is not perfect, and it doesn’t find all cancers,” Morris continued. “We have newer technology that is coming along that actually does increase cancer detection rates and decrease recall rates. The society is supporting research in to those areas.”

Federal Breast Density Bill

Senators Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) and Kelly Ayotte (R-N.H.) recently introduced the Breast Density and Mammography Reporting Act, requiring that radiologists provide notification to patients who have dense breast tissue and communicate the benefit of supplemental screening tests.

The bi-partisan legislation would mandate that the patient summary required under the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) “convey the effect of breast density in masking the presence of breast cancer on mammography, using the provider’s qualitative assessment of breast density.” The bill also calls on the Department of Health and Human Services to focus on research and improved screening for patients with dense breast tissue.

Also introduced in the House of Representatives was a companion bill sponsored by Reps. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), Steve Israel (D-NY), and Mike Fitzpatrick (R-PA).

As efforts to establish a national standard continue, 22 states have passed breast density notification laws. According to Nancy Cappello, founder of Are You Dense and Are You Dense Advocacy Inc and a major crusader for breast density reporting, the state initiatives are a testament to the passion of female patients. “I’m not going out looking for women harmed by their dense breast tissue,” Cappello said. “They are finding me.”

Nevertheless, a number of societies are maintaining a neutral stance regarding the legislation, with many in the imaging community voicing their reservations over a government mandate. Exemplifying the discord surrounding the topic, recent studies published in major journals have noted both the benefits as well as the problems surrounding breast density reporting.[iii],[iv]

“We’re in support of women knowing what their breast density is, but we’re not in support of federally mandated legislation that makes us notify women, because it’s complicated, and I think it’s a confusing issue,” Morris said, on behalf of the SBI. “I can understand the proponents of the breast density bill, that they want women to know. And I fully support disclosure about what’s going on in their body. The problem is we don’t have a better test than mammography to offer.”

Morris stressed the importance of patients’ dialogues with their doctors. “You need to have a conversation with your practitioner, who will try to figure out if you need any other supplemental testing,” Morris said. “For the vast majority of cases, it would be, ‘No.’ But even if patients are recommended to undergo supplemental testing, there isn’t evidence that they would really benefit from it either.”

According to Cappello, the bill’s critics often say they do not want to legislate medicine. “It’s not medicine; it’s critical information about our breast health, and if we could do anything other than legislate it, we would,” Cappello countered. “Voluntary measures don’t work. Sadly, we have to legislate good practice and disclosure of information that women should automatically have. It’s our report. We paid for it.”

Cappello argued “women won’t know to bring up adjunct screening if they don’t know they may need to ask for it.”

“If you look at the USPSTF recent report, the authors spend a lot of time discussing technology,” Cappello said. “I think that’s great. All women should be well informed about the risks and benefits of every technology, whether it’s ultrasound, MR, or tomo, so we can make an informed decision about what we might need to do next.”

“We know that legislation does not ever replace information and education,” Cappello said. “Three sentences in a mammography report do not equate to knowledge about the impact of breast density on a patient, or her other risk factors, like her age or family history. It is important to have those conversations with her doctor.”

Taking account of both the USPTF’s recent screening guidelines and the push for a breast density reporting law, Morris offered her assessment of the complex landscape.

“One group is saying mammography is not perfect, let’s just take it away. The other group is saying, ‘Let’s do other tests to see if there’s anything there,’” she said. “For us, for breast imagers, we’re sort of caught in the middle of these polar opposites, and we want to do the right thing for our patients.”

“We’re caught in a crossroads,” Morris said. “We have so much technology now that we can use to pick up cancer, and it’s really rapidly progressing, but we’re back in the past when the only randomized controlled trials we have are these old studies from mammography that we don’t even practice anymore. Everyone is looking at those trials, but we’re trying to function in the modern situation. How do we use all of these tools to take care of patients? I think the Society of Breast Imaging would like to do it in a thoughtful way that’s evidence-based and not do it based on legislation.”

Cappello acknowledged that breast density notification is only one step in building a more solid patient-physician relationship.

“I would be jumping for joy to have a national standard,” Cappello said. “But that still can’t replace the education that is needed between the patient and her healthcare provider.”

####

Elaine Sanchez Wilson is associated editor of AXIS.

REFERENCES

[i] Miller, AB, et al. Canadian National Breast Screening Study: 1. Breast cancer detection and death rates among women aged 40 to 49 years. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1992; 147.1459-761423087

[ii] Miller AB, et al. Canadian National Breast Screening Study: 2. Breast cancer detection and death rates among women aged 50 to 59 years. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1992; 147.1477-881423088

[iii] Rhodes, DJ, et al. Awareness of Breast Density and Its Impact on Breast Cancer Detection and Risk. Journal of Clinical Oncology, March 2015 DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.0325.

[iv] Kerlikowske K, et al. Identifying Women With Dense Breasts at High Risk for Interval Cancer: A Cohort Study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;162:673-681. DOI:10.7326/M14-1465

Great job, Nancy, of defending the importance of dense breast tissue notification. As a Stage 2b breast cancer survivor, enduring a double lumpectomy, removal of 9 lymph nodes, 16 chemos using 3 different chemo drugs, 33 radiation treatments, and being diagnosed with 5 autoimmune diseases following treatment, it is critically important to disclose dense breast tissue to patients . Not one of my mammograms bore out the fact I had 2 tumors, nearly 4 cms in size and a lymph node that was 4 cms in size because they were masked by my extremely dense breast tissue. Pathology reports indicated they had been growing for a 2-4 year period undetected through mammography, yet none of my doctors spoke to me about my dense breast tissue, and the need for further screening such as ultrasound, MRI or 3-D mammography. Had I not had excruciating breast pain which forced me back to my doctor’s office for an exam, I most likely would not be alive today. I am the first person in my family on either side to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Disclosure of dense breast tissue is key to saving lives, saving trauma to the patient, and millions and millions of healthcare dollars because breast cancer is found at its earliest stage. We don’t have a cure for breast cancer, but we could have a significant impact on breast cancer if people were told of their dense breast tissue, and were afforded an opportunity for additional testing to find their potential breast cancer as early as possible. It is called common sense – we should all be applying it to this medical issue so we could have a profound impact on reducing the effects of breast cancer on our population into the future!

Congratulations Dr Nancy Cappello!

Information should be a right for patients.

We must use all the available tools to fight against malignancy and to improve Early detección.

Women will enjoy looking for your actions in the future.