A new imaging technique has the potential to detect neurological disorders—such as Alzheimer’s disease—at their earliest stages, enabling physicians to diagnose and treat patients more quickly. Termed super-resolution, the imaging methodology combines PET with an external motion tracking device to create highly detailed images of the brain. This research was presented at the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging’s 2021 Virtual Annual Meeting.

In brain PET imaging, the quality of the images is often limited by unwanted movements of the patient during scanning. In this study, researchers utilized super-resolution to harness the typically undesired head motion of subjects to enhance the resolution in brain PET.

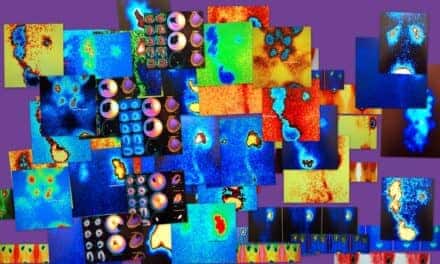

Moving phantom and non-human primate experiments were performed on a PET scanner in conjunction with an external motion tracking device that continuously measured head movement with extremely high precision. Static reference PET acquisitions were also performed without inducing movement. After data from the imaging devices were combined, researchers recovered PET images with noticeably higher resolution than that achieved in the static reference scans.

“This work shows that one can obtain PET images with a resolution that outperforms the scanner’s resolution by making use, counterintuitively perhaps, of usually undesired patient motion,” says Yanis Chemli, MSc, PhD, candidate at the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging in Boston. “Our technique not only compensates for the negative effects of head motion on PET image quality, but it also leverages the increased sampling information associated with imaging of moving targets to enhance the effective PET resolution.”

While this super-resolution technique has only been tested in preclinical studies, researchers are currently working on extending it to human subjects. Looking to the future, Chemli notes the important impact that super-resolution may have on brain disorders, specifically Alzheimer’s disease.

“Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the presence of tangles composed of tau protein,” Chemli says. “These tangles start accumulating very early on in Alzheimer’s disease–sometimes decades before symptoms–in very small regions of the brain. The better we can image these small structures in the brain, the earlier we may be able to diagnose and, perhaps in the future, treat Alzheimer’s disease.”