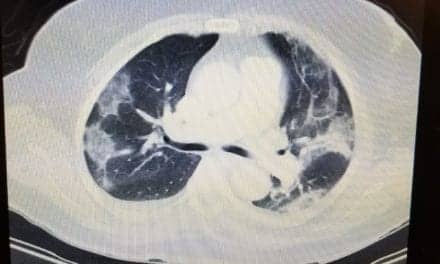

Interim imaging solution at St Luke’s Episcopal Health System, Houston, minor emergency center. Interim imaging solution at St Luke’s Episcopal Health System, Houston, minor emergency center. |

Traditionally, mobile imaging has been used by facilities to relieve overburdened equipment, with the health provider or radiology group leasing a mobile unittypically consisting of a scanner, patient table, control console, and computer, and usually housed in a trailer or similar type of vehiclefor a predetermined amount of time or until the emergency is over.

But there are other reasons that radiology has turned to mobile imaging, including offsetting the cost of the equipment while a market is developed, maintaining service during a building project, and extending service beyond the confines of the hospital, including into remote areas.

Though housed in a trailer, mobile imaging units are not, necessarily, always on the go, nor are they just a transitory solution. As one hospital system in Texas has discovered, mobile imaging can be a viable semipermanent interim solution, providing the capacity it needs, while allowing the flexibility of postponing permanent solutions.

MODEL #1: LEASING

St Luke’s Episcopal Health System, Houston, installed a mobile CT system in September 2002 in its off-site minor emergency center. The facility, which is sited in the same building as a large physician practice two miles from St Luke’s main campus, initially used the physician group’s CT facilities, and soon found, as did the physician groupa large multi-specialty group that offers a full range of radiology services at the sitethat patient loads far outstripped the capacity of the CT unit there. “We had to send the patient to the hospital, where the hospital CT people would treat them like an ER patient,” says Joseph Robertson, manager of the minor emergency centers. “Not only were we outstripping our capacity, so was the clinic next door. They typically would farm out 50 to 60 [patients] a week to another off-site place. They didn’t have the time because they were doing their regular planned CTs, and we had emergent or urgent CTs that they couldn’t do. They did not have the space nor did they have the equipment.” To solve the problem, St Luke’s contracted for a mobile CT unit to be placed in the adjoining parking lot.

St Luke’s Episcopal Health System, Houston, chose an interim imaging solution to add CT capacity for its minor emergency center (right), while an on-site physician practice opted for mobile imaging to add MRI (left). St Luke’s Episcopal Health System, Houston, chose an interim imaging solution to add CT capacity for its minor emergency center (right), while an on-site physician practice opted for mobile imaging to add MRI (left). |

Though a necessary move from a medical and economic viewpoint, there were issues that had to be overcome. Initially, the building’s landlord was against the idea of placing the double-wide trailer in the parking lot. To overcome the landlord’s objections, St Luke’s added a sidewalk, plants, and skirting. To protect patients from rain and the summer sun, a canopy, adjoining the trailer to the main building, has also been added. “You don’t want it to look like a pilot project, because I think the very fact that it looks a little more permanent helps the patient to understand there’s nothing less [capable] about this equipment [compared to] the equipment at the hospital,” says Robertson. In December, near St Luke’s unit, the building’s physician group added its own mobile MRI unit.

Robertson adds that the building’s landlord was not the only entity that had to be sold on the mobile unit. The hospital’s radiologists were a bit leery of contracting for it as well. “They had issues with it because it was not the latest and greatest machine,” says Robertson. “We looked historically at the last 12 months, what type of CTs we sent to the hospital and we explained that basically they were abdominalsome with contrast, some withoutand brain.” Robertson says that the biggest roadblock in getting the unit was finalizing the contract with the company providing the equipment (see box).

There was one requirement that was absolutely necessary for St Luke’s to move forward with the project. The unit had to be integrated with the hospital’s picture archiving and communications system (PACS). This was achieved by running fiber-optic cable from the building to the mobile unit. Like those from the machines in the minor emergency center proper, images supplied by the CT scanner in the mobile unit can be reviewed at St Luke’s main campus and can be archived within its system as part of the St Luke’s patient record.

According to Robertson, patients have had no objections to having their scans done in the mobile unit. He credits the staff with helping to make the unit successful by allaying any patient qualms about its quality. “Once you explain that you are taking them outside because you’ve grown so much you’ve had to move into the parking lot, they understand [and accept] it,” he says.

Because of the long-term contract, St Luke’s is staffing the mobile CT scanner with its own technicians. The unit is fully accredited and the staff follows the same protocols as those in the permanent sites.

The mobile unit has been financially successful, says Robertson, with the scanner more than paying for itself and ensuring efficiency and patient satisfaction. “It’s been a good experiment, so to speak, for us,” he says, adding that he expects the contract will run beyond the initial year. CT is not the only modality available at the minor emergency center, which also has a digital x-ray room.

Though a successful experiment for St Luke’s, equipment leasing is becoming a regular part of the imaging scene. According to a recently published report by the Equipment Leasing Association, Arlington, Va, and RS Carmichael & Co, White Plains, NY, diagnostic equipment leasing is the leading category of health care leasing, accounting for 50% of all health care lease financing. According to the report, in 2002, the US health care equipment leasing market was $5.8 billion and is expected to grow at an 8.5% rate through 2005-reaching $7.4 billion.

Not every radiology practice, however, is turning to mobile imaging as a leasing option; some are using it as a way to test expensive new equipment and leverage it within the market.

MODEL #2: TRIAL RUN

For Radiology Associates of Tarrant County (RATC), Fort Worth, Tex, a 56-radiologist group that provides a full range of services both to local hospitals and in its own outpatient centers, the use of mobile imaging was a different kind of experimentto see if a new technology could be made to pay. When positron emission tomography (PET) became financially viable, RATC found itself in the position of being a trailblazer, purchasing the first unit in Tarrant County in 2000. But the cost and its uncertain profitability meant the practice had to be creative in the way it used this unit. The solution was to make it a mobile unit and move it to RATC’s four freestanding imaging centers in Fort Worth, Arlington, and Southlake that would be offering PET. “At the time we made the decision [to purchase the unit], we decided that if there wasn’t sufficient volume to keep it busy within our own facilities, we wanted the ability to move it to other places outside our market to perhaps capture some share there as well,” says Lynn Elliott, MBA, chief executive officer of RATC.

Lynn Elliott, MBA Lynn Elliott, MBA |

Though having purchased the $350,000 trailer and unit outright, RATC found that as at St Luke’s, the trailer became a semipermanent part of its main site. And though the plan had been to lease the unit to other facilities, this never occurred. “The market proved to be a little bigger than we anticipated,” says Elliott. “We found that the mobile unit was so busy just at our primary location, we didn’t have any time to move it anywhere else.” In May 2002, RATC installed a fixed PET/CT unit at its main freestanding PET site in Fort Worth, and moved the mobile unit to its Arlington office. At the primary Fort Worth office, the practice currently does about 10 PET scans per day. The practice has just traded in its mobile unit for a fixed site PET/CT in Arlington, which does about 15 scans per week. Elliott expects that once the fixed scanner is installed in Arlington, there will be three to four scans per day there, and seven to eight in Fort Worthwhich has been absorbing some of Arlington’s business.

Paula Gibson, RN Paula Gibson, RN |

Elliott says that using PET in a mobile form was a good financial move for the practice and will probably be replicated in the event a new, economically untested modality enters the scene. However, there are some things that he would have done differently if he had it to do over again. “The only thing we would have done differently had we known that the volume was going to be there at our primary site, we probably would have gone fixed site initially,” he says. “But given what we knew at the time, it definitely was the right decision to make, and it’s worked out very well for us.”

The decision to have a mobile unit is not always simply a question of economics, however, but one of providing a needed service to outlying communities.

MODEL #3: COMMUNITY SERVICE

Choosing a VendorIn selecting a mobile equipment vendor, radiology groups and departments are well advised to consider the following:

|

Since 1997, three mobile mammography units from the Comprehensive Breast Center at the Don and Sybil Harrington Cancer Center, Amarillo, Tex, have been making a dusty circuit of 144 sites in the Texas panhandle, the Oklahoma panhandle, the northeastern corner of New Mexico, and southeastern Colorado. Unlike the units used by St Luke’s and RATC, the Harrington mobile mammography units are off-loaded at the various sites, such as churches and community centers. The vans may visit a facility as often as two or three times a month and as infrequently as once a year. Last year, the vans collectively performed 10,000 screening mammograms.? The nonprofit outpatient cancer center has been providing patient outreach since 1989.

Unlike St Luke’s and RATC, which found the move to mobile imaging a profitable venture, Harrington has yet to make it pay. “We have room to grow, we could still expand our program just with the three vans we have, and we’re working on a new campaign to do that,” says Paula Gibson, RN, BSN, administrative director for the Comprehensive Breast Center. “One area we need to work on is the African American community and the Hispanic community. We’ve seen a 10% increase since [1997], but we’re getting flat right now.” Though constantly on the road, Gibson requires each site to have at least 10 people signed up or she will cancel the appointment. To combat cancellations, she is considering combining sites. In an effort to break even, Harrington has contracted with corporate clients to provide screening. Currently, Harrington has 83 corporate clients.

The units are staffed by Harrington employeesusually a technician and a technical assistant. If the program is being offered under the auspices of the Breast and Cervical Cancer Control Program (BCCCP), a federal program administered by the Texas Department of Health, a nurse will go out as well. The vans and all of the personnel are accredited and licensed in each of the four states they serve. Results of the mammograms are read by Harrington’s staff radiologist.

Though a mobile unit, St Luke’s Minor Emergency Center CT scanner has been integrated into the hospital’s picture archiving and communications system. Though a mobile unit, St Luke’s Minor Emergency Center CT scanner has been integrated into the hospital’s picture archiving and communications system. |

Billing runs the gamut from out of pocket to third-party payors to Medicare. Though a regional cancer center, the biggest challenge Harrington has had to face has come from local health maintenance organizations (HMOs). “Although we have such a large service area, we have had challenges with the HMOs because they may not want to designate an out-of-state center as a provider,” says Gibson.”There’s one [HMO, Lovelace Health Plan] in New Mexico that just won’t let us be a provider. That has limited us in terms of collecting fees and providing services to patients.” In some of these areas, including New Mexico’s, Harrington mobile units are the only providers of mammography screening.

According to Gibson, there is about an 18% recall rate. Because of the rural nature of the region it serves, about 98% of the patients recalled come to Harrington for further diagnosis and treatment, making the vans a feeder system to its Amarillo facility’s diagnostic program.

No matter the model mobile imaging follows, it is an alternative that can be used not only to increase market share, but maintain efficiency, raise patient satisfaction, and reach out to the underserved. As the experiences of St Luke’s, RATC, and Harrington show, mobile imaging is more than a creative, short-term solution to challenges facing a department or a practice: it is part of what can make it successful.

?

Chris Wolski is associate editor of Decisions in Axis Imaging News.