In the first MRI-based study to investigate prenatal alcohol exposure, researchers found significant changes in the brain structure of fetuses exposed to alcohol compared to healthy controls. Results of the study are being presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

“Fetal alcohol syndrome is a worldwide problem in countries where alcohol is freely available,” says Gregor Kasprian, MD, associate professor of radiology at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria. “It’s estimated that 9.8% of all pregnant women are consuming alcohol during pregnancy, and that number is likely underestimated.”

Fetal alcohol syndrome is the most severe form of a group of conditions called fetal alcohol spectrum disorders that result from alcohol exposure during pregnancy. Babies born with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders may have specific physical features, learning disabilities, behavioral problems or speech and language delays. According to Kasprian, one in 70 pregnancies with alcohol exposure results in fetal alcohol syndrome.

“There are many postnatal studies on infants exposed to alcohol,” Kasprian says. “We wanted to see how early it’s possible to find changes in the fetal brain as a result of alcohol exposure.”

For the study, researchers recruited 500 pregnant women who were referred for a fetal MRI for clinical reasons. On an anonymous questionnaire, 51of the women admitted to consuming alcohol during their pregnancy.

The questionnaires used were the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a surveillance project of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and health departments, and the T-ACE Screening Tool, a measurement tool of four questions that identify risk drinking. “We provided a safe environment where women could feel comfortable honestly answering the questions,” Kasprian says.

After eliminating some of the fetal MRIs for reasons such as structural brain anomalies and/or poor image quality, the final study group consisted of 26 fetal MRI exams from 24 alcohol-positive fetuses and a control group of 52 gender- and age-matched healthy fetuses. At the time of imaging, fetuses ranged in age between 20 and 37 weeks.

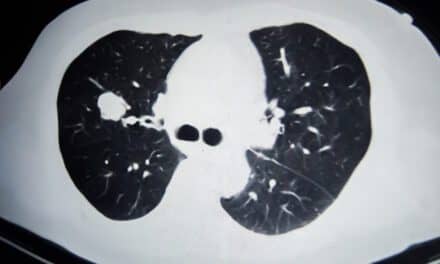

The researchers used super-resolution imaging, which allowed them to create one dataset to re-construct each fetal brain. Next, they completed an analysis of 12 different brain structures, computing total brain volume and segment volumes of specific brain compartments.

“One of the main hallmarks of our study is that we investigated so many smaller sub-compartments of the brain,” says co-author Marlene Stuempflen, MD, scientific researcher at the Medical University of Vienna.

The statistical analysis revealed two major differences in the alcohol-exposed fetuses compared to healthy controls: an increased volume in the corpus collosum and a decreased volume in the periventricular zone. “This is the first time that a prenatal imaging study has been able to quantify these early alcohol-associated changes,” Stuempflen says.

The corpus collosum is the main connection between the brain’s two hemispheres. Stuempflen noted that it is fitting that this very central structure is affected, because the clinical symptoms of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders are highly heterogenous, or diverse, and cannot be pinpointed to one specific substructure of the brain.

“The changes found in the periventricular zone, where all neurons are born, also reflect a global effect on brain development and function,” she says.

The researchers say finding a thicker corpus collosum in the alcohol-positive fetuses was surprising because the corpus collosum is thinner in infants with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

“It appears that alcohol exposure during pregnancy puts the brain on a path of development that diverges from a normal trajectory,” Kasprian says. “Fetal MRI is a very powerful tool to characterize brain development not only in genetic conditions, but also acquired conditions that result from exposure to toxic agents.”