Siemens Healthineers’ AI-Rad Companion, used to examine chest scans, performed as well as traditional lung function tests to identify patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), an umbrella term that includes emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and other lung diseases. Showing that the artificial intelligence software works is the first step toward possibly using chest scans to quantify the severity of the lung disease and track the progress of treatment, say the researchers, led by U. Joseph Schoepf, MD, director of cardiovascular imaging for MUSC Health and assistant dean for clinical research in the Medical University of South Carolina College of Medicine.

Diagnosing emphysema and classifying its severity have long been more art than science,” Schoepf, says. “Everybody has a different trigger threshold for what they would call normal and what they would call disease.”

And until recently, scans of damaged lungs have been a moot point, he adds: “In the past, if you lost lung tissue, that was it. The lung tissue was gone, and there was very little you could do in terms of therapy to help patients.”

But with advancements in treatment in recent years has come an increased interest in objectively classifying the disease, Schoepf says. That’s where artificial intelligence and imaging could come into play.

In the study, researchers went back and looked at the chest scans and lung function tests of 141 people. Chest scans aren’t currently part of the guidelines for diagnosing COPD, Schoepf says, because there hasn’t been an objective means to evaluate scans. However, he anticipates a role for imaging scans if it can be shown that they offer a benefit in terms of objectivity and quantification.

Philipp Hoelzer, customer engagement manager with Siemens Healthineers, says that having an objective measurement could help in assessing the value of new treatments or drugs. The Siemens Healthineers team sees the program as a way for artificial intelligence to work in tandem with the clinical expertise of radiologists, he says.

“Taking away manual, repetitive tasks, like those that require a lot of measurement, is of great benefit to a radiologist, especially when reading cases that may have 20 or more nodules,” Hoelzer says. “Interpreting the images, and the abstract thinking that goes along with it, will remain with the radiologist.”

The program can also offer a concrete aid to doctors trying to impress upon patients the necessity of making changes. It can create a 3D model of the patient’s lungs, showing the existing damage.

“If you could visualize it and provide the information in image terms, you could better communicate with the patient and hopefully nudge the patient into smoking cessation or lifestyle changes,” Hoelzer says.

A potential additional benefit is that AI-Rad Companion automatically looks for problems across multiple organ systems, including measuring the aorta and bone density. As Schoepf moves into a prospective study phase, he’ll be examining whether the artificial intelligence finds things that humans miss. And it can be easy for humans to miss problems that they aren’t specifically looking for, he says.

“We’re told the patient has these types of symptoms, and then we basically go look for stuff that could explain those symptoms,” Schoepf says. “So, we’re often blind to things that do not necessarily relate to the organ system we’re interested in.”

Further, addressing the dynamically changing healthcare environment, significant efforts are currently in the final stages to train the artificial intelligence software in the detection and characterization of COVID-19-related lung changes. Hopefully, this would provide physicians with a tool to better differentiate the rather non-specific lung findings of COVID-19 pneumonia from other infectious or inflammatory lung disorders and more objectively quantify the extent of disease.

In terms of the measures for which it was originally developed, Schoepf says MUSC Health will test the system for 3 months before determining whether to deploy it more extensively. With a regional network that now includes hospitals across the state, it could be a useful tool in standardizing care.

“It’s a great chance for patients to get better care. We have world-class radiologists here, but these systems add a little extra,” Schoepf says.

Read more from MUSC and find the study at American Journal of Roentgenology.

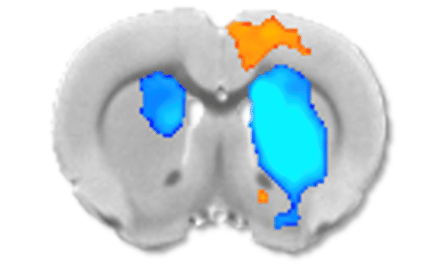

Featured image: These scans show the lungs of a 68-year-old woman with slight emphysema, top, and a 65-year-old man with severe emphysema, bottom. From left to right, each row shows a CT image, a CT image that includes artificial intelligence calculation, and a 3D model. Credit MUSC.