|

More than any other imaging procedure, mammography has given radiology a public face. Public service advertisements on television, on radio, and in print urge women to get a yearly mammogram. Lawmakers have recognized mammography’s value by passing legislation guaranteeing Medicare recipients access to the procedure.

With this high profile, however, come the challenges and criticism associated with any very-public endeavor. Though mandated by Congress, mammography remains woefully under-reimbursed by insurers and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Mammographers are the most sued specialists in radiology, affecting both morale and access. And, in a score of reports over the last year, the media has questioned both the effectiveness of mammography and the radiologists who administer it.

These very public trials reflect the controversies raging within the specialty, including the issues of subspecialization, the shrinking pool of mammographers, reimbursement, new technology, and the overselling of mammography. And while radiologists and, specifically, mammographers agree that these are problems, they disagree on how to solve them.

Issue No. 1: Subspecialist vs Generalist Readers

In the September issue of Radiology, University of California-San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center radiologists Edward A. Sickles, MD, and Dulcy E. Wolverton, MD, and Katherine E. Dee, MD, now at the Department of Radiology at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, reported that radiologists specializing in mammography recognized more cancers, particularly early stage cancers, and had lower recall rates than general radiologists.

The study involved more than 47,000 screening and more than 13,000 diagnostic mammographic examinations. In general, mammographers were almost twice as likely to detect a cancer than a generalist. The study also found that recall rates for mammographers were much lower, 4.9%, compared to generalists, 7.1%. And though it may be safe to assume that specialization is the answer, lead author Sickles, who is a professor of radiology and section chief of breast imaging at the UCSF, is quick to point out that his study can only be considered preliminary, and not the final word on the issue.

And though specialization might make sense in large urban areas like San Francisco, in smaller markets or in smaller groups, it may not be practical. “Subspecialization, like any systems paradigm, has its advantages and disadvantages,” says R. James Brenner, MD, JD, director of breast imaging at the Eisenberg Keefer Breast Center, Tower-St Johns Imaging in Santa Monica, Calif, and clinical professor of radiology at UCLA. “Advantages usually can be successfully engaged in [within] a larger group where volume and resource allocation can be matched. All systems require some redundancy to account for vacation time and other off-the-front-line responsibilities. When one becomes too subspecialized, then that person’s contribution to redundancy in the system is compromised.”

Though subspecialization is an attractive ideal, it could also compromise patient access, says Valerie P. Jackson, MD, FACR, John A. Campbell Professor of Radiology, residency program director, and chief of breast imaging at the Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. “Subspecialization would undoubtedly improve the accuracy of mammography,” she says. “However, the tradeoff would be decreasing access because there are already too few radiologists who subspecialize in mammography and we can only do so many cases.”

She also cautions that solutions such as double reading and the use of computer aided detection (CAD) systems have their own set of limitations. “Double reading has been shown to improve detection of cancer, sometimes at the expense of a higher false-positive rate, but not always[it] depends on how the double reading is handled,” she says. “However, with the manpower shortages we have, it becomes very difficult, if not impossible, to have double reading in many practices. CAD systems have been shown to pick up additional breast cancers missed by radiologists, but they often lead to much higher false-positive ratesespecially when used by radiologists who don’t have the confidence or experience to throw out’ the many false-positive areas that get flagged with CAD.”

Subspecialization could have other benefits. It can be an easy way to build the group’s local profile and decrease legal liability, says Brenner. However, even with the benefits it affords large groups, he admits, subspecialization could have a downside. “Some radiologists are reluctant to surrender any skills, for fear of future employment opportunity restrictions,” he says.

But with all the benefits subspecialization could bring, particularly in higher accuracy rates and less legal liability, there is the question of where these specialists will come from.

Issue No. 2: The Case of the Vanishing Subspecialty

Radiology as a whole, and mammography in particular, is facing a severe and well-documented manpower shortage. According to the American College of Radiology (ACR), this shortage may take up to 10 years to correct even if additional slots can be created for radiology residents. The shortage is not a product of a lack of interest on the part of medical studentsradiology is one of the most popular specialties among residentsbut funding caps. “The caps are actually just put there,” says Ellen B. Mendelson, MD, professor of radiology and chief of the Breast Imaging Section, Northwestern University Medical School/Northwestern Memorial Hospital Lynn Sage Comprehensive Breast Center, Chicago. “CMS will not reimburse facilities beyond the caps that have been set. It’s a complicated thing. They’re imposed on all residency positions. What facilities look for is some sort of economic aid in supporting their training program. And money comes from the federal government to support the education of physicians in training.”

According to Mendelson, schools can offer as many slots as they want. It is all a matter of funding. Residency stipends, which include salaries and health benefits, average about $60,000. “We can try to find funding,” she says. “There are so many regulations and so many stipulations right now. We can apply for more help. Will [the government] come through? It’s possible, we don’t know.” Mendelson and her colleagues are currently in the process of evaluating 300 applicants for seven radiology residency positions for 2004.

The shortage of mammographers not only is a result of too few slots, but also has been caused by a lack of incentives to enter the specialty. “The disincentives derivative of the current economic climate for breast imaging is likely to affect [residents’] decisions,” says Brenner. “So, as a secondary consequence, the lack of incentives to go into breast imaging may have a negative impact on access to mammography, in terms of both specialty selection, as well as group or institutional commitment to increasing resource allocation.”

This lack of incentive is primarily a function of mammography’s low reimbursement rates and high stress level, which is caused by its high legal liability. “Unless we solve the reimbursement and medicolegal problems associated with breast imaging, we are unlikely to attract residents into the field and women’s access to mammography will be further compromised,” says Jackson.

Issue No. 3: Who Should Pay?

Perhaps the most contentious issue facing mammography is who should pay for the procedurethe government, insurers, or patients.

For Brenner, when mammography became a public mandate, the die was cast, so public monies have to be used to support the specialty. “To underfund the mandate [will result in a de facto] tax on providers,” he says. “Actual cost surveys have indicated that reimbursement is grossly inadequate at health care institutions. These are not only the very venues where most Medicare beneficiaries receive their care, but are the ones that serve as training centers for future breast imaging specialists. To ignore such costs for a population designated to receive the benefits of the program is tantamount to abandoning the commitment that Congress has made. Lip service to providing mammography to the population in this country is no substitute for adequate reimbursement. Those who seek to divert funds from a proven technology [such as mammography]and there remain a minority who contend that the benefits are not sufficiently provento elusive targets of investigation sometimes emerge from those who were not benefited by the technology. It is somewhat ironic that outcome goals for more expensive [procedures, such as] chemotherapy are far below benchmarks for mammography, though the controversy continues to haunt the latter, and not the former.”

Mendelson’s outlook on the problem of reimbursement spells doom for the public mandate Brenner talks about. Instead of seeing greater access to mammography, Mendelson speculates that there could be decreasing access with groups such as several in New York City offering mammograms as a cash-only, nonreimbursed examination. “The groups in New York that have taken themselves out of the reimbursement cycle are doing just fine; if you are providing services to people whose incomes are high and who have the ability to pay, there’s no reason to reduce the cost to those people,” she says. “Somebody who pays $120 to go and have their hair colored and cut can afford to pay $375 for a mammogram. For those people for whom mammogram costs are a hardship, will it impair access? Probably.”

But this dire scenario of examinations only for a wealthy elite may not come to pass. Some believe that high-quality, efficient, and affordable mammography could be realized through the efficiency of a new generation of digital imaging equipment.

Issue No. 4: Is the New Digital Technology Worth the Cost?

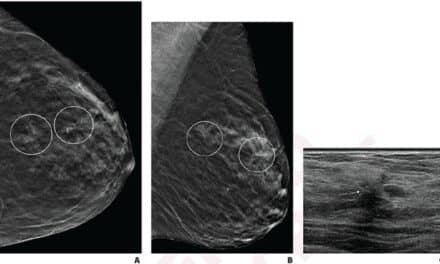

In the September issue of the American Journal of Roentgenology, John Lewin, MD, et al reported that both digital and film mammograms showed cancers the other format missed. Film was slightly better, but the difference was statistically insignificant. The advantage for digital mammography over conventional film mammography is efficiency, according to Lewin, an associate professor and codirector of breast imaging at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver. “The value of digital is not going to be in terms of finding more cancers at screening, no more than the value of computed radiography for the chest is in finding more lung cancers,” he says. “The value of going digital is in terms of functionalityelimination of film and processors, digital archiving, unlimited copies, electronic image transfer. Technologists can process patients faster on digital than on film, so throughput per machine is increased. Also, while my study looked only at screening, digital magnification viewsused in diagnostic mammography, not screeningin my opinion, are superior to those taken on film.”

Michael Linver, MD, director of mammography for X-Ray Associates of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and associate professor of radiology at the University of New Mexico, sees a bright future for digital mammography, with its ability to leverage resources by transmitting studies to outside mammographers. But, he says, its efficiency and cost-benefits have not yet been realized. “Right now, it’s still too expensive,” he says. “The workstations are still so badly designed, they’re not very efficient to use. Given the small reimbursement, time becomes a critical issue. You can’t be efficient the way the current workstations are set up, plus the machine is just too expensive; it costs you around $800,000 to set up one machine with a workstation with all the bells and whistles. [However,] I think competition will drive that down.”

But even when the technical problems are solved, the promise of efficiency and lower cost of the technology may still not make it practical. “Whether or not mammography is worth it depends on your setup, including your patient volume, the relative costs of technologists, floor space, machines, and how many film units you would have to replace,” says Lewin.

No matter how advanced or efficient the technology, it is still only as good as the mammographer making the interpretation. “What we found in our study was that any difference in technology is obliterated by the variability in reading by the radiologist and by random effects of positioning by the technologist, so human factors are key,” says Lewin. “Other studies have shown that just under half of the cancers missed by mammography are detectible in retrospect and the others are not visible, so clearly there is room for improvement on both sides. CAD may help the interpretation side. The technical side may require some major change from the mammography paradigm of a single radiograph of a compressed breast before a noticeable improvement can be made.”

Identifying a quality reading may be as difficult as developing a new technology. “How do you train people to do a better job? Some of it is just experience,” says Linver. “Even if you know what you’re doing and do it well, if you don’t do it all the time, you lose those skills. That’s why I think a certain minimum number should be required at a much higher level than it is now.” Linver adds that an effective, high-volume practitioner would be reading at least 3,000 studies a year.

Issue No. 5: Is the Modality Worthy?

Fundamental to the controversies facing mammography is whether it is as effective as it claims to be. For Leonard Berlin, MD, FACR, chairman of the Department of Radiology, Rush North Shore Medical Center, Skokie, Ill, mammography has promised more than it can deliver. This is reflected in rising insurance and lawsuit rates. “On one hand, if you look at the last decade, we see a continuing rise in malpractice litigation, [but] as far as conduct of radiologists goes, the American College of Radiology and other professional organizations have worked very hard to increase the performance of radiologists,” he says. “I don’t think that anybody can doubt that radiologists in 2002 do a better job reading mammograms than they did 5 and 10 years ago. In spite of that, the number of suits and severity of suits increasewhy? Obviously, there are only two things that can cause an increase in litigation: negligence of the doctor or the injury caused. And the negligence hasn’t increased; if anything, it’s gotten better. Therefore, let’s focus on the injury to the patient and my thesis is that our success in promoting mammography by emphasizing its values has strengthened the injury cause more than our success in reducing radiologic errors. We’ve reduced radiologic errors, but the promotion we’ve done on mammography as far as establishing its efficacy is far greater than our ability to decrease the errors.”

Berlin says that statistical studies, which have been widely circulated in professional journals and the news media, have muddied the waters, usually for the worst. “If you ask whether the early diagnosis of breast cancer reduces mortality, as some commentators have said, that remains one of the most disputed issues in medicine today,” he says. “It’s intuitively obvious, but it remains markedly resistant to scientific validation. There have been a number of articles on both sides in the scientific literature. There are various statistical biaseslead time bias, length bias. It all tends to skew the survival figures. There was an article in the New England Journal of Medicine 2 years ago that reviewed 63 articles between 1995 and 1997 on statistical errors; they found 48% of the articles had mistakes in how they calculated the statistics.”

The result of all of these contradictory reports and inflated statistics is misinformation and fear, which has been exploited by the media. “There was a survey published in the New York Times in January ’01 -40% of women feared dying of breast cancer, but only 4% of them do; 4% of women have a fear of dying of heart disease and 36% of them dothese are the misperceptions,” says Berlin. “There’s a study out of Dartmouth University, a survey of women, and they overestimated dying of breast cancer by 20-fold; they overestimated the value of screening mammography in reducing this risk by 100-fold.”

The answer to the statistical bias that has resulted in the overselling of mammography is simple: honesty. “We have to tell the truth to the American public that there are controversies out there; that we don’t know the absolute truth,” says Berlin, who describes himself as pro-mammography. “I think we will never know the absolute truth, because no matter what statistical study is done, there are always flaws in the study. There is no proof that mammography does not save lives, and until or unless there’s proof that it doesn’t save lives, then I think we have to recommend mammography.”

Berlin has already begun his campaign to get the truth out, introducing a resolution at the September ACR meeting. “The American College of Radiology, while it should continue to support and recommend mammography, should nevertheless undertake a public relations campaign that accurately informs the public about the pros and cons of mammography,” he says. “Yes, they should still recommend it, but they should tell the truth about mammography, tell both sides of the mammography situation, and encourage women to have mammography, but in the last analysis, a woman has to decide for herself.”

The public relations campaign is necessary, says Berlin, because mammography is here to stay and will continue to be provided in the same way it is now until science can offer something completely differentsuch as molecular studies or a blood test similar to the one used in prostate cancer screenings.

For all of his qualms about the effectiveness of mammography, Berlin is supportive of it. “Let’s look at mammography as an opportunity to find your breast cancer early, and let’s look at it as a good opportunity for a cure,” he says.

What’s the Answer?

There is no dispute among radiologists as to the value of mammography. Even those most critical are dedicated to their specialty. If there is one common theme linking the most pressing issues, it is funding. Without it, there will be no mammographers to provide the tests that millions of women rely on for their continued good health. As Mendelson points out, “We value mammography, but we don’t want to pay for it.” Without the financial incentive to lure the best and the brightest, Congressional legislation notwithstanding, more and more residents will enter other, more lucrative fields of medicine and radiology. The question of where this money should come from will probably continue to fuel the debate and be as dependent on political and philosophical outlook as economic and medical realities.

As Berlin suggests, the ultimate future of breast health may lie outside the realm of mammography. A recent report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences may prove him to be prescient. The publication issued findings by researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York and the University of Washington-Seattle who have found a breast cancer gene that could aid in detection of breast and other cancers.

C.A. Wolski is associate editor of Decisions in Axis Imaging News.